THE MAP AND THE TERRITORY

CONTEMPORARY ART GALLERIES – UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT | FEB 14 - MAR 23 2023 |

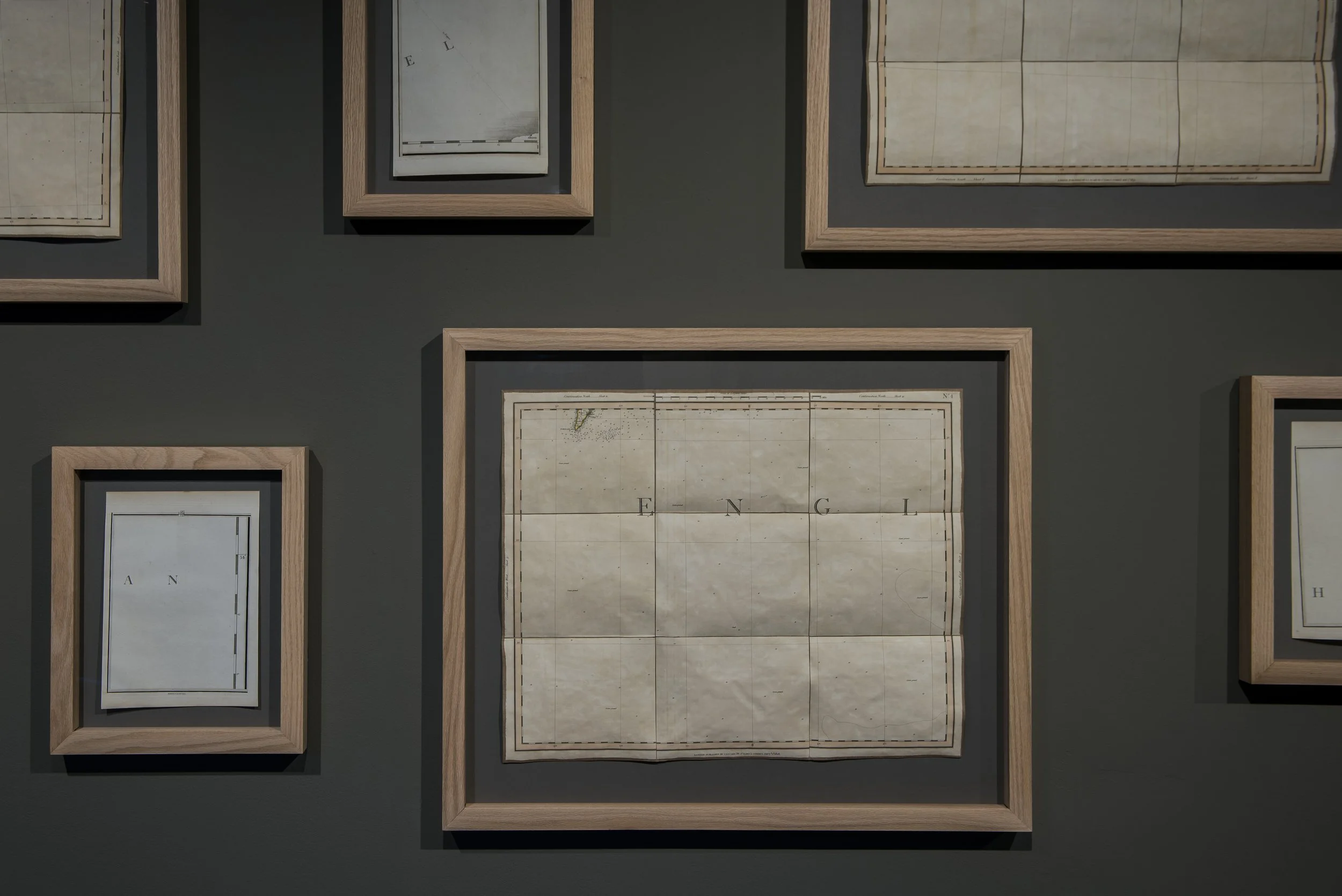

Drawing its title from mathematician Alfred Korzybski’s adage that “a map is not the territory it represents,” [1] this exhibition comprises an archive of constellations that were erased by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in the 1920s, and a collection of blank maps of the English Channel. Considered together, these works trouble our understanding of maps, and the systems by which we measure and represent space.

Both the erasure of constellations and the coordinates of these maps reflect European systems of organizing space and the visual field. In The Darkness of the Present, Morawetz reflects upon a decision made by a European man about which constellations were legitimate under an international body. Alongside these erased constellations, she has placed artefacts of measurement, and a series of found maps which are startlingly blank, yet strategically, politically and historically loaded. The collected maps reference Lewis Carrol’s epic and absurdist poem The Hunting of the Snark, in which a group of characters set out on a voyage with a blank map, which will eventually end in darkness.

Home was the center of the world because it was the place where a vertical line crossed with a horizontal one. The vertical line was a path leading upwards to the sky and downwards to the underworld. The horizontal line represented the traffic of the world, all the possible roads leading across the earth to other places.

— John Berger

THE HORIZONTAL AXIS

We think we know what a map is. But if the idea of a map seems self-evident, it is only because we have been so thoroughly trained to interpret a flat grid as a corollary of three-dimensional space. In fact, a map is an abstraction that erases as much as it reveals. That is, it smooths out the messy, culturally nuanced and lived experience of place, in order to make it appear coherent, systematic, and intelligible.

We learn to extrapolate space from these surfaces, and the distortions, expansions, and geopolitical as well as poetic hierarchies that they inculcate. There are many powerful, expedient fictions at play in maps: the Mercator projection, for example, enlarges small European nations and shrinks equatorial ones — very often formerly colonized territories — and places the northern hemisphere at the top of the page and the southern hemisphere at the bottom. While these distortions were the product of prioritizing shipping routes, making the map fit for purpose, we cannot help but infer a hierarchy from the map’s layout.

The abstractions at the heart of cartography are political, and historically contingent. Jordon Branch tells us that new methods in mapping, developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, were integral to the emergence of the sovereign nation state as we understand it today. The spatial expanse of sovereign terrain in medieval Europe was far messier, and far less exclusive, than modern cartography suggests. European sovereign rule tended to be recorded in inventories and lists that worked from the center of sovereign rule outwards. The fifteenth century, however, saw the translation of the Grecian thinker Ptolemy’s Almagest and Geography — which mapped the celestial and terrestrial spheres respectively. This brought about a shift in the European geographical imaginary: whereas medieval mapping was a way of accounting for the known world, cartographic technology created a system that could be applied to unknown areas. [2]

Inasmuch as “forms of authority not depicted in maps were undermined and eventually eliminated, while map-based authority claims became hegemonic,” [3] the map was a tool of emergent European territorialization — that is, the strategic creation of territories using an array of visual, cultural, political and military technologies. In all its excisions, consolidations and expedient simplifications of space, European maps created territories; maps are ways of codifying space not only so that it can be navigated, but also apportioned, allocated, argued over, seized and sold. The map may not be the same thing as the territory that it represents, but in its embodiment of authority and its expediency in reaching hitherto unknown destinations, it has been an essential tool of territorialization.

It’s hard not to see the legal doctrine of terra nullius here. This doctrine – namely that ‘empty’ and ‘unoccupied’ space can be seized and ‘improved’ by British colonists – rendered the invasion and ongoing occupation of Indigenous territories such as Australia (where the artist is from) and North America (where the exhibition is staged) ‘legitimate’ under European systems of law. It is not hard to read, in the very blankness of the map and the disappearance of constellations that this exhibition foregrounds, a stunning disregard for what is there, a convenient and ordinary manoeuvre that enabled all kinds of cultural and political violence, past and present.

The ocean may appear blank on these maps, but territorial waters are the subject of enormous contest and tension: the space that these maps depict is one of the busiest shipping routes in the world. The English Channel holds French, British and International waters. In the narrower part of the straight (near Dover) the French and British butt up against one another.

In Britain’s break with the European Union, questions of sovereign territorial rights have re-emerged in this zone. In 2021, French fishermen threatened to blockade a small English harbor in protest over fishing licences in the wake of Brexit; Britain sent two gunboats to the area, and the French responded in kind. In the same year, 27 people drowned in the English Channel attempting to reach Britain in a bid for refugee status. This prompted a territorial spat between the two sovereignties that had little to do with the loss of life, and a lot to do with the politics of Brexit, the rights and responsibilities of nation states. Those who lost their lives were from African and West Asian countries, formerly colonised or otherwise exploited by these two European powers. This oceanic blank space, quick to be claimed for fishing rights and just as quick to be disavowed from humanitarian responsibilities. Blankness is political.

THE VERTICAL AXIS

Like most of us, I have memories of being shown how to connect points of light in the night sky, an exercise that entailed filling in the gaps (which are in fact vast tracts of space) with a story — Orion’s belt, the Pleiades, the Scorpion. The sky is a site of both imagination and deep acculturation: constellations have shared cultural meaning and convey all kinds of information. The images that we glean from the arrangement of stars in the sky have little to do with those stars, or their relationship to one another. But they do tell us where we stand: the constellation tells you the location of the viewer, not only literally (the viewer’s geographical location), but also culturally (the viewer’s cultural roots, education, language and shared meaning with those around them). John Berger wrote that the placement of the stars in the sky forms part of an axis connecting us to the arrangement of the dead buried beneath our feet. This, he suggests, is what anchors us in the world.

The Darkness of the Present is about how we view ourselves on the earth, as terrestrial beings. It commemorates a particular history: in 1925 Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte was appointed by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) to do an audit of the night sky. Founded in 1919, the IAU was an organization that, while claiming the international in its very name, was largely European in its membership. Delporte’s task was to create a list of officially sanctioned constellations, and this necessarily entailed leaving out a multitude of others. This audit was largely about erasing those constellations that overlapped with others. That is, the goal was the neat division of the celestial sphere into a single, contiguous map of the night sky.

Morawetz’s commemoration of these discarded constellations takes several forms: a series of black-on-black drawings, an arrangement of brass rulers in the configurations of constellations, and with a pair of posters that, when placed side by side, read TO ORDER THE STARS | AGAINST THE WILL OF THE SKY; on their verso, the 48 constellations are listed; an enigmatic wall text reads THE DARKNESS OF THE PRESENT IS NOT EMPTY.

If the stars — or the patterns of their constellation — correspond to our present, the darkness that surrounds them is not empty, but rather full of constellations that might no longer or not yet be there [...] The darkness of the present is not empty, but rather it carries within it the possibility of a different constellation, of a universe different from the one we know, or the presence of other planets still preserved by the darkness of time.

— Daniel Blanga-Gubba

THE MANY-CENTERED WORLD

Not only subjects of myth and meaning-making, constellations have long been used as a means of navigation for many communities. In this exhibition, this inventory of deleted constellations pairs with maps unnervingly empty maps of the sea. Containing all the nomenclature of direction but none of the anchor points that might situate oneself upon it, The constellations almost disappear into the darkness upon which they are drawn.

What is an empty map? On a blank sheet of paper, we search for markers of place, folding and unfolding, spinning around, calibrating. Surely, a map with no markers is not a map at all. These blank maps speak to the dizzying adventure turned terrifying loss of control that is at the heart of Lewis Carrol’s Hunting of the Snark. The unmooring sense of a loss of coordinates mirrors the vanishing of 48 constellations. It is fitting, then, that Carrol’s poem ends in darkness.

Carrol’s poem is about nonsense and a loss of meaning. Morawetz’s work is, in some ways, about the opposite of this: hers is a deep and sustained consideration of what ‘conventional signs’ denote, and how they have come to mean what they mean. The vexed relationship between the idea and the thing is at the heart of these and many other works by Morawetz. In 1:1 (After Umberto), for example, she made a map of the room in which the work was to be exhibited on a 1:1 scale, a performative enactment of Borges’ 1982 essay “On the Impossibility of Drawing a Map of the Empire on a Scale of 1 to 1.” In trying to spread the enormous map of the gallery floor across the actual space that it represents, the absurdity of the proposition becomes obvious. In 2019 she walked across France in a reperformance of an historical journey originally begun in 1792, to measure the curvature of the earth’s surface, from which to devise the standardised measurement of the meter (one-ten-millionth of the distance from the North Pole to the Equator). Every day of her journey, the meter changed length ever so slightly – a fluctuation that reveals the corporeal and contingent nature of standardized measurement. It's about the poetic precision of systems of measurement, and their utter absurdity.

Unlike the informal plasticity of language, where meaning evolves with usage, the markers of distance and time are agreed-upon, and typically unchanging signs put in place by official bodies. But as the very concept of the map and the territory emphasizes, these systems are not what they represent.

DOCUMENTATION BY DANIEL BUTTREY

[1] Alfred Korzybski. 1995. Science and Sanity: An Introduction to Non-Aristotelian Systems and General Semantics. New Jersey, USA: Institute of General Semantics (5th edition). 58.

[2] Jordan Branch. 2013. The Cartographic State : Maps, Territory and the Origins of Sovereignty. New York : Cambridge University Press.

[3] Branch, The Cartographic State. 6